Peninsula Lifestyle magazine

June/July 2016

Lindbergh Strawbale Home by Jill Buhler

At first glance, the house at the end of the long, dirt road seems as conventional as its neighbors. A casual visitor wouldn’t guess there’s anything unusual about it until he spots the glass frame on the wall and wonders why his hosts would hang a picture of straw in their dining room. If he looks closer, he sees that the frame is actually a glass door and that the straw behind it is real: the door is there to showcase the main component of the walls in this innovative strawbale home tucked away in a very private spot on the Kitsap Peninsula.

At first glance, the house at the end of the long, dirt road seems as conventional as its neighbors. A casual visitor wouldn’t guess there’s anything unusual about it until he spots the glass frame on the wall and wonders why his hosts would hang a picture of straw in their dining room. If he looks closer, he sees that the frame is actually a glass door and that the straw behind it is real: the door is there to showcase the main component of the walls in this innovative strawbale home tucked away in a very private spot on the Kitsap Peninsula.

That’s the first of the surprises.

At first glance, Erik and Mara Lindbergh seems as conventional a young couple as their neighbors. It isn’t until you’re sitting in Erik’s office and you notice the autographed photo of astronaut Scott Carpenter among the aerospace luminaries in the pictures lining the wall that you suspect there might be a connection between the articulate, energetic man behind the desk and the Lindbergh name. And you would be right.

Erik is the grandson of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh. He and Mara are as unpretentious and unique as their home. Despite the celebrity surrounding them, the Lindberghs lead a simple, down-to-earth life contrary to Erik’s high-flying heritage.

Erik is the grandson of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh. He and Mara are as unpretentious and unique as their home. Despite the celebrity surrounding them, the Lindberghs lead a simple, down-to-earth life contrary to Erik’s high-flying heritage.

Born in 1965 in Santa Barbara, Erik moved with parents Jon Lindbergh and Barbara Robbins to the Pacific Northwest when he was two weeks old. He’s been here ever since. “I tried to move away several times, but it didn’t stick,” he laughs. Three of those times involved stints as a “ski bum” during and after high school, twice at Crystal Mountain and once at Sun Valley, where he washed dishes, flipped burgers and tended bar to pay his way.

Mara, who has roots in Montana but was raised on Bainbridge Island, met Erik in high school. After graduation, Mara encouraged Erik to follow her to Evergreen State College where she was studying early childhood development. She later changed to message therapy and now has a private practice on Bainbridge Island.

Erik studied political ecology at Evergreen, but, like his grandfather, found college too constricting and left after two years. With the encouragement of a friend who had the flying bug, he decided to go to flight school. Erik was 9 when his grandfather died, but he remembers his visits well. “He was pretty comfortable with kids,” he recalls, “and encouraged me to learn to wiggle my ears, but there was no encouragement to become a pilot. All the attention that centered on his flights was pretty intense for our family, so they tended to go in other directions.” Except for Erik.

When Mara heard Erik’s plan, she said, “Find a flight school where there’s a massage school and I’ll go with you. So he did.” They landed in Colorado where Erik earned his Aeronautical Science degree from Emery Aviation College.

At age 21, Erik was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a progressive autoimmune disease that led to his near-total disability by age 30. During the disease’s progression, the pair moved several times. They bought a home in Eugene, Oregon, fixed it up, sold it for a profit, repeated the process on Bainbridge Island, and rented a beach house on Marrowstone Island while Erik was a flight instructor at Port Townsend and Bremerton Airports. At one point, when it was too painful for Erik to walk and he could manage only an occasional odd job, the couple lived in a yurt at a friend’s organic farm and Mara’s message therapy practice provided most of their income.

Happily, times now are much better and thanks to several surgeries and a breakthrough biotechnology drug in 1999, Erik is working and traveling again.

Happily, times now are much better and thanks to several surgeries and a breakthrough biotechnology drug in 1999, Erik is working and traveling again.

Not surprisingly, Mara and Erik are passionate about health and ecology. When the couple decided to move back to the Kitsap Peninsula to be closer to family, they wanted a home that used natural materials and had a smaller environmental impact than traditional stick-built homes. That meant they would have to build their own. The plan was to find enough acreage to build two houses, share the well and the cost of infrastructure with Mara’s mom.

Searching for property that had good southern exposure, Mara remembered seeing a parcel at the end of a road in a small waterfront community. But that was years ago. One evening Mara and her mom were driving around when, “We finally find this road,” Mara says. “It’s almost dark, it’s pouring down rain, just pouring buckets—you could hardly see. We get to the end of the road and there were ‘For Sale’ signs on them. I broke out in goose bumps. I looked at my mom and said, ‘This is where we’re going to live,’ and she said, ‘Mara, turn the car around, it’s pouring down rain, let’s just get out of here!’ She was not convinced.”

Erik recalls, “Mara and her mom saw this overgrown sign at the end of this long dirt road, it was raining and dusky and she was spooked by it. But the next morning when I looked at it I knew it was our place.” “We had an intuition about this area,” Mara adds. “There’s something about this community being small and off the beaten path that drew us.”

They bought two 2-1/2 acre parcels, which left them just $40,000 to build their house. But what kind of house? Erik and Mara looked at earthship houses that were interesting, with walls made of rammed earth filled tires, and plaster. They investigated Cob and Rastra® construction. Then they went to a workshop on Whidbey Island. “Someone was building a strawbale house and massage studio. It was absolutely gorgeous, lots of light. We fell in love with the structure and the fact that it could be a community building process like a barn raising,” Mara explains. “That was very thrilling to us. We did most of the work with family, friends and neighbors, and in the process, made a lot of new friends.”

That was 10 years ago. Alternative housing was just starting to develop on the Peninsula. “We built the first strawbale house in Kitsap County,” Mara grins. Did they have trouble with the permit process? “We zipped through in two weeks,” she laughs. “We handed them a whole stack of literature proving that it was an OK thing to do. We came in really prepared, and got our permit in a couple of weeks, which seemed amazing for such an unusual house.”

To save costs, they used recycled windows and doors. “We just scraped and salvaged and did lots of our own labor,” on the 900 sq.’ home, says Mara.

About five years ago, as the family began to grow, they decided they needed a larger home. So while Erik was retracing his grandfather’s legendary 1927 Spirit of St. Louis transatlantic flight on its 75th Anniversary, flying solo from Long Island to Paris in May, 2002, Mara was at home looking for a builder.

“I told Erik I was going to Port Townsend to find a builder because, in my mind, that’s where all the innovative building was going on,” Mara explains. “I knew there were Rostra® houses and cob buildings and other strawbales being built and I thought, ‘That’s where I’ll find a builder.’ I got there, had breakfast at the Salal Café, and Bruce’s business card was on the bulletin board by the restroom. I took it off, called him right then and said, ‘Do you build strawbales?’ He said yes and the rest is history!”

It was also serendipitous. Mara and Erik found the perfect partner in Bruce Glenn, owner of Terra Sol Design and Building, whose motto is “Restoring harmony, balance and health in our living environment.”

It was also serendipitous. Mara and Erik found the perfect partner in Bruce Glenn, owner of Terra Sol Design and Building, whose motto is “Restoring harmony, balance and health in our living environment.”

Bruce, who has extensive building experience using a variety of materials, became an advocate of healthy homes in 1988 when walked into a house and had an allergic reaction due to building materials’ off-gassing urea formaldehyde. The episode started him on a cleansing program, a search for healthy building materials and a new career goal. “I’ve always had a passion for passive solar homes and I wanted a better building envelope for people and the environment,” he says. He researched all alternative construction techniques—Rastra® and Dursol (insulated concrete forms), passive solar earth-bermed homes (earthships, underground dome homes), geodesic domes, cob, and timber frame structures. Bruce combines the best materials for the particular topography and home design, but loves bringing the local indigenous materials like stones, trees, straw and clay into the home. “It saves the planet by reducing the transportation cost for shipping materials and reduces the energy embodied in the manufacturing process,” he adds.

“In 1991 there were few products available,” Bruce recalls. “Earlier, I had heard of strawbale construction but kind of blew it off like most people do. I thought, ‘Right, it’s like the big, bad wolf, blow your house down, it disappears.’ But I reviewed it again in 1991 and realized the R value is 300 times that of a standard home. If we can reduce the amount of energy it takes to manufacture and heat our homes, there’s a huge beneficial impact on the planet’s resources.”

Since then, Bruce has built several strawbales, including 13 in Colorado—the first permitted strawbale homes in the state. In 2001, Bruce moved to Port Townsend and researched strawbales up and down the West Coast and Canada. He found several on the Peninsula including a 6,000 sq.’ Montessori School in Sequim that was doing fine after 10 years. Another in Quilcene had water damage during construction and afterwards with floods, but a recent inspection when the home was sold found no signs of mold or damage.

When Mara talked to Bruce on the phone, she was thrilled. “We hit it off right away,” recalls Mara. “Bruce has an amazing ability to design something and to make it work. He’s also extremely sensitive as to what you want to do.

“We wanted the person who was going to be on site with us every day to be respectful of our space, of us, of the land and the impact of the project. And Bruce is certainly on top of that.”

The goal was to add on space that was “inspiring.” Mara and Bruce worked together during the design process as Erik was on his transatlantic trip. “Erik is so unassuming,” says Bruce. “I didn’t know where Erik was until I saw him land in Paris on Good Morning America. He just said he was on a business trip. That’s all he ever told me…not that he was flying across the Atlantic by himself!”

The goal was to add on space that was “inspiring.” Mara and Bruce worked together during the design process as Erik was on his transatlantic trip. “Erik is so unassuming,” says Bruce. “I didn’t know where Erik was until I saw him land in Paris on Good Morning America. He just said he was on a business trip. That’s all he ever told me…not that he was flying across the Atlantic by himself!”

The first concept involved adding on another story, which would also capture a distant water view. But it didn’t feel right to the Lindberghs. “It looked added-on. It was too much space and wasn’t quite right. So we revisited it and came up with bumping out the living room. There was something about the round shape we really liked. We scratched our heads a lot and said ‘How do we do this?’ Bruce finally just sketched it out and we said, ‘Yeah, that’s it!’” The plan added about 1,400 sq.’ of living room, two bedrooms, bathroom, laundry and mud rooms.

The Lindberghs lived in the house until the main front wall was taken out, then they moved to their old yurt, which sits on their property and is now a pilates studio rented by a friend of Mara’s. The building process took 9 months after the design was completed and involved several changes along the way. “The building process was really organic for us,” says Mara.

“We couldn’t make all the decisions until we lived in the house. Like where should the stove go? We planned for it in another spot, but when I was standing in the kitchen I realized that I can see the water from the center of the room, so we put the stove there. I can’t know that on paper. That’s the great thing about Bruce. He’s able to work with us. He had to be a little patient with us throughout the process.”

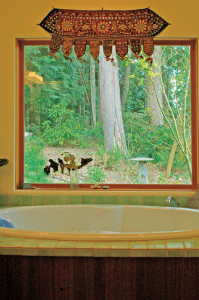

When Bruce suggested that several small horizontal windows designed for the living room be replaced with a large picture window, though, they had to act fast. “We had one day to make our decision,” Mara grimaces. “That brought on a whole discussion about where we would put our books, stereo and TV. We had a whole conversation about what we really want to be doing in this room. So we put the TV in the back room and went for the picture window. It was a good decision.”

Rather than vinyl windows (PVC polyvinylchloride), which contain dioxins (dioxins are known carcinogens) and other unhealthy compounds, Bruce suggested Milgard’s fiberglass windows with vertical grained veneer. “We’re reducing the dioxins by using these windows,” Bruce says. “They are triple or quadruple the cost of normal windows, but the environmental impact is greatly lessened.”

Rather than vinyl windows (PVC polyvinylchloride), which contain dioxins (dioxins are known carcinogens) and other unhealthy compounds, Bruce suggested Milgard’s fiberglass windows with vertical grained veneer. “We’re reducing the dioxins by using these windows,” Bruce says. “They are triple or quadruple the cost of normal windows, but the environmental impact is greatly lessened.”

To be eco-friendly, they again used recycled materials. The heart pine floor came from a whiskey distillery in Kentucky. The beautiful Mahogany door frames are salvaged from yacht cradles from Asia. One of the great finds was a set of three huge windows left over from Bill Gates’ house construction on Mercer Island. Window sills are made of indigenous Douglas fir that Erik milled.

In keeping with Bruce’s preference for using local building materials, straw for the walls came from Cenex. They are the same kind of bales used in storm water control. In the Lindbergh home, bales are placed on a standard foundation with a wood floor system as opposed to using a clay floor sealed with oil that is prevalent in the Southwest but rare in the Pacific Northwest. Construction consists of a wood frame using the bales as the walls. The bales are then covered with hand-troweled cement-based stucco with a lime finish that can be colored or left a natural white. Although the roof can be made of any material, the Lindberghs chose metal.

Due to the insulating quality in the strawbale construction, radiant floor heat, a wood-burning stove and the use of solar energy keep the home warm. Large windows in the living room allow the sun’s rays to heat the interior plaster throughout the home and the stone hearth beneath the wood stove. Along with storing heat, the hearth adds architectural interest. “To define the hearth space we called on Dave Myers, a friend and local artist, for help,” says Mara. “We knew the design had to have motion. The room is round and sticking something square in it didn’t feel right. We were at the sub-floor stage, so Dave drew different shapes on the floor and we lived with them for awhile. One day he said, ‘I’ve got it. The edge needs to look like a river.’

“There are so many beautiful things you can bring into a house. This was not particularly expensive compared to doing something with tile, but it adds such a nice play of elements. The stones behind the stove protect the wood from the heat and add a nice visual effect. And it never occurred to me that those rocks heat up and provide the added bonus of reflexology when you press your feet on them.” Erik and Mara relish their involvement in the home’s construction. “People who choose to build strawbales are happy they did because of their involvement in it,” Mara believes. “It’s a different level of involvement than choosing your countertop. The choices are narrow in most building projects. In this project, we really got to feel our way into it and make a lot of decisions along the way. It’s a phenomenal thing to do.”

“There are so many beautiful things you can bring into a house. This was not particularly expensive compared to doing something with tile, but it adds such a nice play of elements. The stones behind the stove protect the wood from the heat and add a nice visual effect. And it never occurred to me that those rocks heat up and provide the added bonus of reflexology when you press your feet on them.” Erik and Mara relish their involvement in the home’s construction. “People who choose to build strawbales are happy they did because of their involvement in it,” Mara believes. “It’s a different level of involvement than choosing your countertop. The choices are narrow in most building projects. In this project, we really got to feel our way into it and make a lot of decisions along the way. It’s a phenomenal thing to do.”

Bruce agrees. “People who choose to live in a natural house often want more input. People who want an ecological home, not just a strawbale home, want a healthy environment.”

The Lindberghs are happy with their home. “People comment on how comfortable this house is and I think that speaks to the strawbale and thick walls that make it feel ‘old world-ly,’” says Mara. “We’ve remodeled houses and built houses and now we’re ready to just enjoy our lives. We want to be here a long time.”

With the hard work done, Erik can concentrate on his career as a public speaker, his philanthropic activities, his art and his flying.

A talented artist, Erik creates wood and metal sculptures and furniture. His pieces grace a Bainbridge Island gallery, the Museum of Flight in Seattle, NASA headquarters, and the homes of private collectors such as Jay Leno. His burl wood sculpture, “Escape from Grey Matter,” is featured on the front cover of the summer 2006 edition of Sculptural Pursuit magazine. He designed six retro mini-rockets that were the first bronze sculptures ever to fly into space when they went aloft aboard Spaceship One, winner of the Ansari X PRIZE—another of Erik’s passions. SpaceshipOne designer Burt Rutan prohibited the sale of space-flown items, but agreed to let Erik auction off one for charity. It brought $15,000 to the Lindbergh Foundation, of which Erik is vice chairman. He gave four rockets to colleagues and kept one for himself, displayed with its letter of authenticity on his office wall.

The Lindbergh Foundation, in its 29th year, gives grants to researchers working on projects in a variety of disciplines that demonstrate his grandparents’ vision of Balance between technological advancement and preservation of the environment.”

“If you picture a balance scale with technology on one side and the environment on the other side you quickly realize that quality of life is somewhere near the fulcrum of that scale. If you put too much weight on one side or the other you end up out of balance.” This ethic, instilled from exposure to the foundation’s work over the years, is what inspires Erik in all of his work.

In 1996, Erik helped launch the X PRIZE Foundation, a non-profit organization aimed at changing the way people think of space travel. Fashioned after the Orteig Prize, won by his grandfather in 1927, the X PRIZE awarded $10,000,000 to the winner. “We wanted to prove that space travel isn’t just for government or big business but that private industry and the common person will be able to fly into space,” explains Erik. “It’s expensive now, but that’s true of every new form of transportation: cars, trains, even bicycles. As space travel becomes cheaper and more reliable we will start to realize the potential benefits of things like: space solar power, mineral resources, and medical advances that are held in check by the high cost and unreliability of our current government-funded space transportation systems. We are now evolving the X PRIZE Foundation into a world-class prize institute to create additional radical breakthroughs for the benefit of humanity. We are actively researching the feasibility of new prizes in space, energy, medicine, education, nanotechnology, and prizes in the social arena.”

His latest business venture debuts in August, but he won’t elaborate except to say that it will change the way that pilots own and fly aircraft. If it is anything like the other projects he is working on it will have a transformative effect on the industry. For the past four years, public speaking has been Erik’s main income source. Capitalizing on his diverse career and background, he talks to civic and governmental organizations, corporations, museums, clubs, and “anybody who’ll listen,” he says with a smile.

On being a celebrity, Erik says, “It can be a burden, and it took me a long time to realize how it can also be an asset. In aviation circles where I’m well-known, it used to be a real pain. People come up to me, shake my hand and exclaim, ‘I never thought I’d get a chance to meet a Lindbergh!’ right to my face. Now I just try to smile, be positive about it and surf off the energy that they are getting from the encounter. It’s a double-edged sword because I can also leverage this legacy to accomplish positive change in the world, like what we are doing at the X PRIZE Foundation and the Lindbergh Foundation.”

On being a celebrity, Erik says, “It can be a burden, and it took me a long time to realize how it can also be an asset. In aviation circles where I’m well-known, it used to be a real pain. People come up to me, shake my hand and exclaim, ‘I never thought I’d get a chance to meet a Lindbergh!’ right to my face. Now I just try to smile, be positive about it and surf off the energy that they are getting from the encounter. It’s a double-edged sword because I can also leverage this legacy to accomplish positive change in the world, like what we are doing at the X PRIZE Foundation and the Lindbergh Foundation.”

Although he doesn’t see himself as a motivational speaker, his audiences are captivated by his stories of his journey into disability and back out again. His message is a positive one: “I feel fortunate to live in an age of technology that enabled me to have a second chance at life. I don’t know if I will get a third chance, so I try to live every day to its fullest.”

Photography by Jill Buhler